I’ve worked on Alaska conservation for going on 15 years now. This career fell right into my lap, when the finance company I was working for was sold twice in twelve months resulting in my small satellite office shutting its doors. That summer I spent a month and a half in Alaska on vacation, and ended up meeting some people that would change the course of my working life.

Before that fortuitous turn of events (talk about turning lemons into lemonade!), I had been disengaged to a large degree from the outdoors. The ten years I spent working in a cubicle and eventually my own office (that’s a big deal in the corporate world) were focused on career advancement, bigger paychecks, and not so much on fishing, hunting, camping, or the other things I enjoyed in my younger days.

So, this post is a bit of a flashback. But it’s also something that’s totally relevant today. In the late 1970’s, my parents began taking my brother and me to Ely – the town at the edge of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) in northeastern Minnesota. Being a baseball junkie, I was always a little ticked off that our vacations interfered with playoff games. But, with three and a half decades gone by, I can now fully realize that trading a few baseball games for the weeks that we spent together as a family in the wild north woods was a steal of a deal.

We’d head north from our home amidst the farms and fields of southern Minnesota in our station wagon, pulling our Lund fishing boat that was packed full with a monstrous (and heavy) canvas tent, all our food, clothes, fishing gear, and probably a bunch of stuff we never used. Upon arrival in Ely, we’d stop to see our friends who lived in a cabin in the woods outside town. Paul was a fishing guide extraordinaire and his wife did housekeeping at a few resorts in the area. He’d give us the fishing report, and we’d check in at the same resort we always stayed at – to prepare for our weeklong adventure in the BWCAW. In advance of seven days away from the conveniences of what was then the “modern world,” my brother and I would enjoy some ice cream sandwiches, and I’d spend some of my lawn mowing money on playing some video games (the stand-up console kind, not Xbox) and music from the jukebox in the game room at the resort. My brother, ever the more passionate angler, would spend his money on bait and lures.

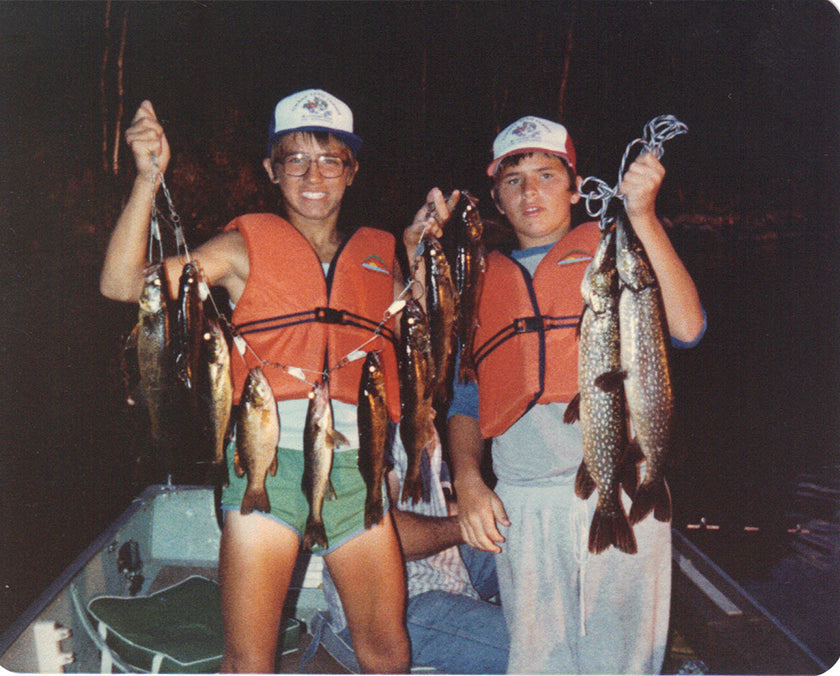

Early the next morning, Paul would load us all into his enormous old Chevy Suburban and we’d drive down a stretch of highway that eventually turned into a gravel road before sometimes finishing as a two track path with tree branches scraping each side of the rig. Over the years, we visited several different lake systems. Some of the most memorable trips were to Jackfish Bay on Basswood Lake – a large lake on the Canada border. It took many hours by boat to travel the 30+ miles through Moose, Newfound, and Sucker Lakes before traversing Prairie Portage on the Canada border and continuing in Basswood Lake through a maze of islands to reach our campsite in Jackfish Bay. We’d set up camp and get to fishing as fast as possible. Walleye were our primary target, but we caught lots of pike and bass as well. If the weather was hot, we’d swim. If the fish weren’t biting, we’d pull to shore and pick blueberries. If the weather turned nasty, we’d ride out the storm under the tent while thunderstorms rolled through. Once, lightning struck right across the small bay from our camp site. When it was clear, we paddled across to find a pine tree that had been blown to bits by the strike. We’d see eagles, ducks, deer, and even moose. And in the evenings, around a camp fire, we’d listen for the call of the loons or the howl of wolves. We’d have fish fries, and we’d drink water straight from the lake (with Kool Aid, of course). At the end of the week, Paul would show up and we’d take the long boat ride in reverse, back to civilization. We’d take proper showers at the resort, and head to Paul’s house for “attitude adjustment hour,” which meant we kids enjoyed some Pepsi while the adults enjoyed some age-appropriate beverages. Stories were told of the fish landed and lost, and we’d pledge to return the next summer to do it all again. Which we did – every year until I finished high school.

Those memories came back to me recently as I was approached to lend a hand in a campaign to protect the Boundary Waters from the threat of copper mining on its southern boundary. Together with a team of passionate and talented people I’ve had the privilege of working for many years to protect Bristol Bay, Alaska from the proposed Pebble Mine (the battle’s not over, by the way). This time, it’s personal. When asked to help bring anglers and hunters into the fight for the Boundary Waters, it was impossible to say “no.” Don’t mess with my family’s personal memories or the place that in hindsight gave me my first experiences with true wilderness and eventually my view toward public lands that now provides my career.

The thing is, my experience in the Boundary Waters is unique to me – but it’s far from unique. The BWCAW is the most-visited Wilderness in the country, with over 250,000 people enjoying its clean waters and healthy forests annually. If you’ve been there, you know how special it is. If you’ve not been there, what are you waiting for? In the meantime, help protect the BWCAW. There are some places that are simply too valuable to risk.

Find out more at www.SportsmenForTheBoundaryWaters.org.